The Taku Watershed

Spanning four and a half million acres of remote wilderness, the Taku Watershed is one of the most ecologically intact and biodiverse regions on Earth. This vast landscape—stretching from alpine snowfields and rugged mountain peaks to lush forests, unspoiled rivers, and thriving coastal estuaries—remains entirely undeveloped.

In an era marked by species loss, declining salmon populations, and climate change, the Taku stands out as a rare ecological refugia—intact, resilient, and thriving. Its diverse habitat supports a wide range of wildlife, including grizzlies, brown and black bear, moose, wolverines, wolves, lynx, caribou, mountain goats, sheep, deer, steelhead trout, and all five species of salmon. All native species are still present and abundant, and the Taku’s natural bounty continues to support the traditional lifeways of Indigenous peoples, as it has for generations.

Located at the heart of the Alaska–British Columbia transboundary region, the Taku is Southeast Alaska’s most productive salmon producing watershed and the largest completely intact watershed on the Pacific coast of North America. Protecting its wild character and ecological integrity is a central mission of Rivers Without Borders.

The Tulsequah Chief Issue:

The infamous Tulsequah Chief mine sits on the banks of the Tulsequah River, a major tributary of the Taku in northwestern British Columbia, just upstream from the Alaska border. Since it was abandoned in 1957, the mine has been leaking toxic acid mine drainage and heavy metals into the watershed; almost seven decades of pollution for an otherwise pristine river system.

This contamination threatens critical salmon habitat, fish and wildlife populations, and the health of the entire Taku watershed, one of Southeast Alaska’s most important salmon bearing waterways. Despite repeated requests from Alaska to close and clean up the abandoned mine site, the pollution continues unabated.

In 2015, British Columbia’s Mines Minister visited the Tulsequah Chief mine site and committed to its remediation. Since then, only preliminary work has been completed with no transparent timeline for when on the ground clean up will commence.

This watershed lies within the traditional territory of the Tlingit people on both sides of the border: the Taku River Tlingit First Nation (TRTFN) in Atlin, B.C., and the Douglas Indian Association (DIA) in Juneau. Both TRTFN and DIA, along with the Southeast Alaska Indigenous Transboundary Commission—a coalition of 15 Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian Nations—have been leading advocates for the cleanup of the mine.

Alaska’s congressional delegation, commercial fishing associations, community leaders, and others have long urged British Columbia to prioritize remediation of this scarred landscape. The Tulsequah Chief mine remains the sole source of industrial pollution in the Taku watershed. Addressing this issue is essential to safeguarding the river’s future.and ensuring that the TRTFN’s Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area declared for much of the watershed is ecologically meaningful.

You can access the latest information on the remediation of the Tulsequah Chief mine here.

Current Situation - New Polaris

While early-stage work continues at the Tulsequah Chief mine site, the long-promised full cleanup has yet to begin. Rivers Without Borders remains committed to pushing for a transparent timeline and meaningful, on-the-ground remediation.

At the same time, a new threat has emerged. The proposed New Polaris gold mine, a project of Canagold, is being planned just downstream on the Tulsequah River—near the confluence with the Taku. This development risks further degrading vital salmon habitat and disrupting the region’s fragile ecological balance.

This is a cross-border issue with profound implications for communities, economies, and ecosystems on both sides of the Alaska–British Columbia border. We call on the Government of British Columbia to fully address the longstanding pollution at the Tulsequah Chief site before considering any new mining projects downstream.

You can access the latest information on New Polaris here.

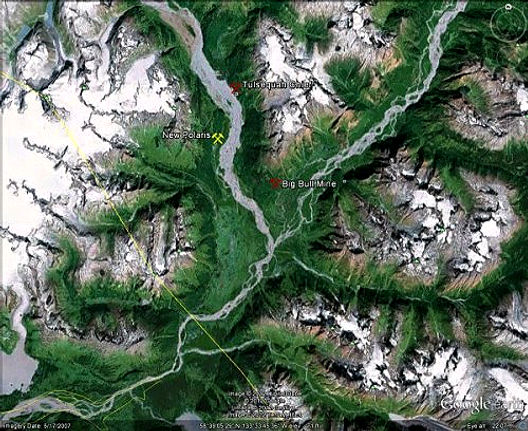

The Tulsequah River tributary of the Taku River flows down from the upper left of this satellite image. The mainstream Taku River flows in from the upper right and down through the bottom of this image after the two rivers converge. The border with Alaska is the thin yellow line slanting down left to right. Flannigan Slough, the Taku Watershed system's best wild salmon habitat, is right below the convergence of the two rivers. Juneau, Alaska is down below this map on the left where the Taku flows into the Pacific Ocean.